Awaiting the outcome of his secret trial in a cold Soviet prison, the Old Bolshevik Rubashov reflects on a long and bloody career as Party revolutionary. In his meditations, Rubashov attempts to make sense of the arc of history. How could, despite the idealism of Soviet socialism, reality unfurl to produce a merciless authoritarian state? How could the culmination of his and his comrades’ revolutionary efforts result in Stalinism? He makes no attempt to excuse himself of his own involvement in the violent work of achieving the liberation of the proletariat. Though fate has cast him into his cell, he just as easily could have ended up on its opposite side.

The output of his musings is an explanatory framework for human political development, christened the theory of relative maturity.

Rubashov’s theory posits that human societies do not follow a linear trajectory to political and economic emancipation, but rather swing back and forth – much like a pendulum – from dictatorship to democracy, contingent upon a given society’s inexperience and mastery over their technological environment. Dictatorships emerge from the early stages of material development, when societies are ‘immature’ and new technological capabilities are alien to them; democracies are only earned once the masses have conquered these technologies.

With every new technical development, there is a subsequent and protracted period of collective learning. Political maturity can thus never be measured against some objective standard: it can only be assessed relative to the stage of the society’s material development. Once mass-consciousness rises, and political subjects understand their new technologies, as well as the consequences thereof, often taking years, decades, and generations, democracy is ultimately and inevitably attained. This lasts until the arrival of a new technological epoch, whereupon the masses are then cast back into relative immaturity as tyranny resurfaces.

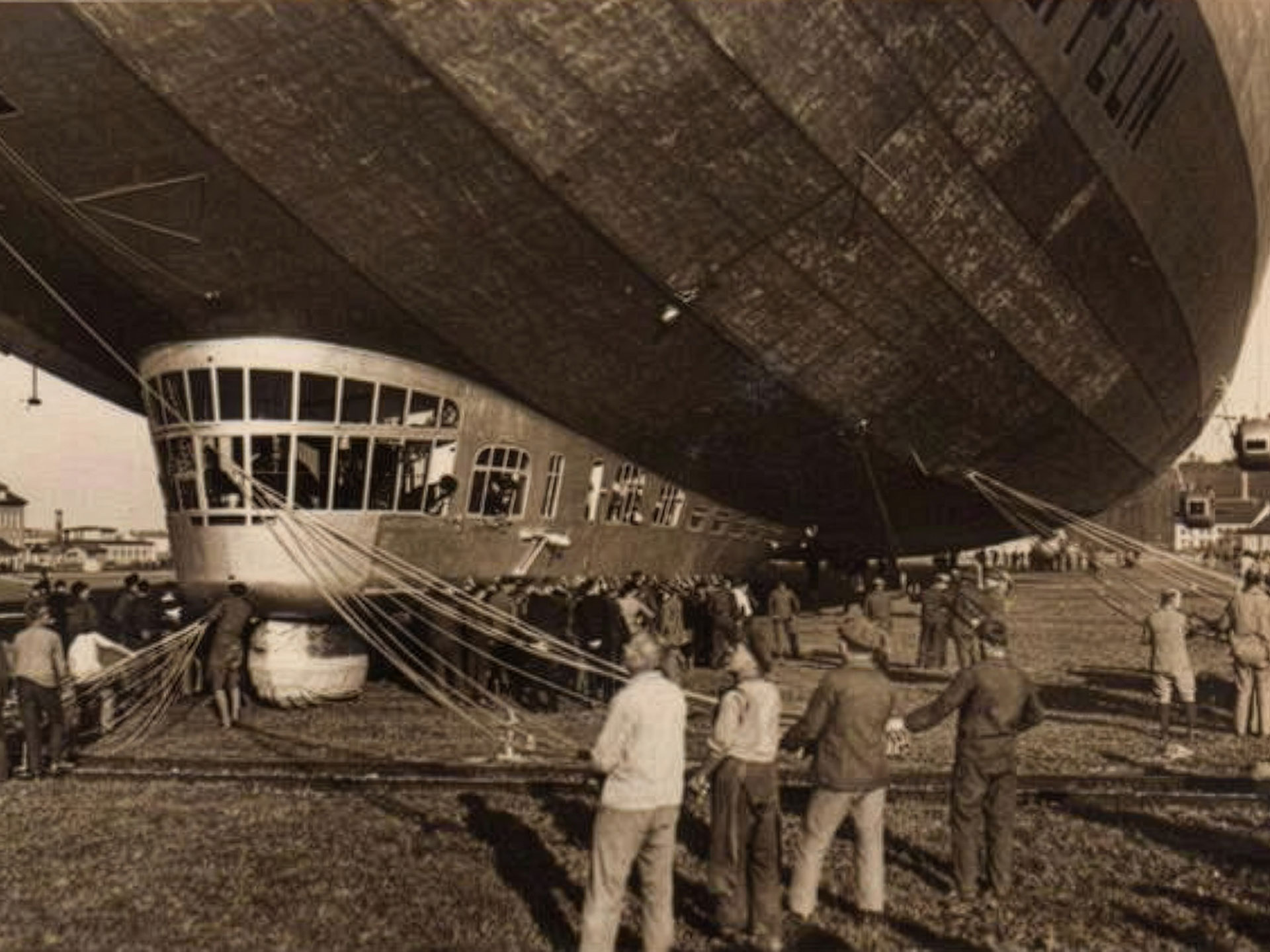

The Industrial Revolution opened up the possibility of global supply chains and ostensibly limitless economic growth, yet brought with it new forms of war, conquest, and repression. The dawn of the twentieth century was accompanied by the full force of new age weaponry, brought to bear on untold casualties during the First World War. Chemical weapons and heavy artillery the counterweight to penicillin and widespread commercial travel. How many farmhands from across Russia’s great expanse were sent to the Eastern Front to witness this awesome power firsthand – to see their comrades thrown into the meatgrinder and succumb to these Industrial Age horrors? How many then, fewer still, did return to their motherlands to see the grounds they once sowed be torn apart by great metal machines, swapping their ploughs for pickaxes? The speed with which industrialization transformed societies into something totally alien gave scarce time for this transition to be properly comprehended. The resulting vacuum, borne in the tempest of nationalism and ideology that marked the early twentieth century, was easily filled with the order and security of empire.

The flaw in the Soviet system, Rubashov argues, was its presumption that mass-consciousness scaled with technological development, and that all what was required to achieve liberation was the forcing out of the old guard to bring the idyllic society into being: The exorcism of the Rousseauian man’s corrupting socio-material influences. Similarly, the naïve idealism of the liberal West did not escape Rubashov’s analysis – itself equally incapable of making sense of the loom, the steam engine, the radio. “The capitalist system will collapse before the masses have understood it.”

However totalising and however accurate, the treatise Rubashov sets forth holds considerable value for making sense of our time. The early 1990s saw the end of the Soviet bloc and the advent of the Internet. Once thought to be the tools with which the world chart a path to unambiguous liberalization, the age of the digital has, in almost equal measure, been harnessed for repression, control, and global strategic contest. Social media burgeoned in the 2000s to do untold damage to democracy, to interpersonal relationships, and to the human psyche. No sooner than when we began to collectively understand these effects did the hype of the next thing – the vogue and mystique of artificial intelligence – usurp social media’s place. For decades, we have blanketed the world in hydrocarbons and pesticides while remaining ignorant to the latent health effects of microplastics and forever chemicals: the former having penetrated the blood-brain barrier and the latter rendering the entire planet’s rainwater undrinkable.

We’re looking ahead, we don’t have time to look back. Move fast and break things until nothing but a trail of destruction is wrought in our wake. Quantum, gene-editing, the outer limits of space – let’s break those next.

What is perhaps distinct about our time to that of Rubashov’s is the uniquely countervailing effect our modern technologies have towards mass enlightenment. The diminution of attention spans, social fracturing, and simulacra of modern social media, the sustained cognitive impairment from environmental pollutants, the asymmetric warfare capabilities offered by the surveillance state and lethal autonomous weapons systems: all work against our global political development and force the pendulum backwards, closer to tyranny.

As these cascading challenges scale, and our collective ability to understand and intervene diminish, the call for authoritarian leadership may resound ever more clearly. Our modern global economic system is a vestige of the Bretton-Woods Post-War lull. Its short-term prosperity is unravelling, and the world’s governments can only kick a can so far. The reverberating whiplash unto the next generations that will soon be felt is nothing short of unbridled intergenerational warfare. In times of uncertainty, fear, mistrust, and hostility rouse the authoritarian resident within each of us – a call which is beckoned by those willing to push demagoguery and domination.

It is unclear if Arthur Koestler, the author of the 1941 novel Darkness at Noon in which Rubashov and the theory of relative maturity are located, is arguing vicariously through the Old Bolshevik, or merely confining the theory inside his character as a form of cathartic release for his own participation in bloody revolution. Rubashov, a political prisoner, is of course doomed: the outcome of his trial known before it has begun. Rubashov dies, and so too, the theory of relative maturity with him, never reaching its complete expression. Koestler, however, survived through Stalinism to see the other side of the Iron Curtain. A journalist-cum-intelligence operative fighting against European fascism in the 1930s, Koestler became disillusioned with communism’s ideals after his imprisonment in Spain, where he bore witness to almost daily executions of his fellow revolutionaries. The Party’s continuous devaluing of human life and ugly commitment to ends-justifying-means saw him abandon his support shortly before the Second World War. Koestler then joined the British government’s anti-communist foreign propaganda wing, funding much of his work and casting a long shade of doubt as to the integrity with which he advanced Rubashov’s thesis.

As a totalising framework for history and human political development, the theory of relative maturity is not recognised among the ranks of Hegel’s Spirit, Fukuyama’s end of history, or Diamond’s guns, germs, and steel. Yet, its depiction of humanity as in perpetual tension with its technological environment – and thus itself – reveals valuable insight into our current moment. At this eleventh hour, will we overcome our collective inability to properly understand our techno-historical standing? Or will the pendulum thrust us backwards into a dark age of despotism?