For someone who was born years later and thousands of kilometres away, the story of 1970s Argentina is simply unfathomable. Because from an early age we’re told that the mistakes of the past aren’t meant to repeat themselves. And yet Argentina from 1976 to 1983 mirrors Nazi Germany, for instance, in so many frightening ways.

Up to 30,000 people were murdered during the last of Argentina’s six dictatorships in the 20th century. Most of these people were never seen again, their bodies buried, burned or disposed of during the so-called “death flights” that the Navy carried out across the Atlantic Ocean.

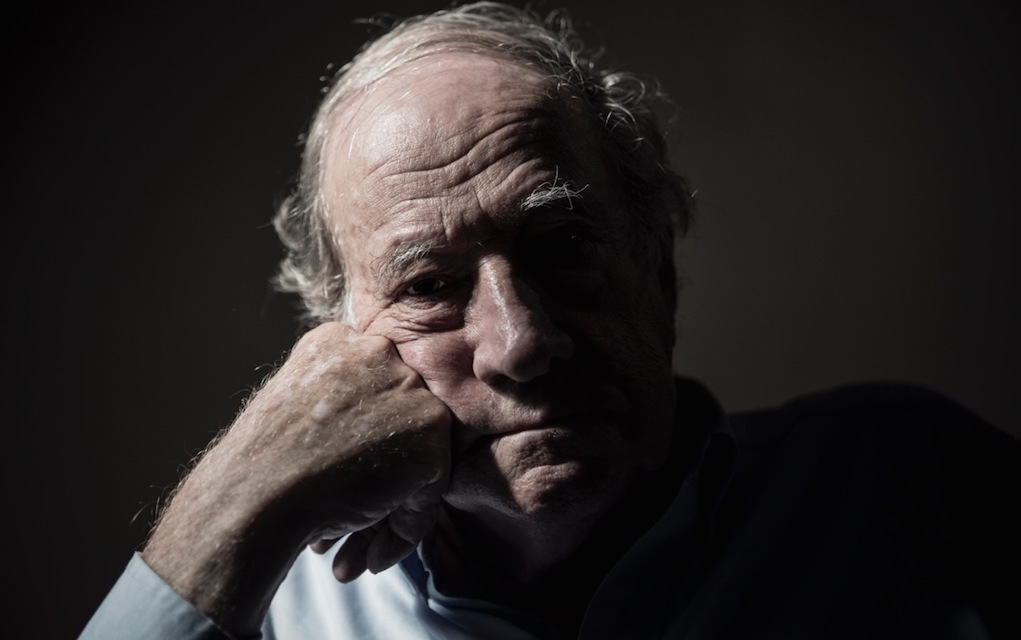

General Jorge Rafael Videla’s regime almost got away with it, according to former editor of the The Buenos Aires Herald, Robert Cox. The local press said nothing and an atmosphere of fear ruled society with an iron first. “Silence is health,” the generals would say. “They made one big mistake,” says Cox. “And that was to think that the relatives of these people were willing to accept that their loved-ones wouldn’t be coming home.”

The Herald had long been an outsider in the local media game, which is perhaps why it came as a surprise to the military that this small English-language daily refused to toe the line with self-censorship.

https://vimeo.com/116973849

Jayson is currently running a Crowdfunding campaign to fund Messenger On A White Horse. For more information on how you can help, please click here.

Under Cox’s leadership, the paper’s newsroom was opened up to the relatives of the so-called “disappeared” who flocked to the Herald each day in their dozens. On the side, Cox and his team would churn out carefully-worded editorials that called on the military to return the country to rule of law and to respond to pleas for information from distraught relatives across the country.

Some of them, like the Mothers and Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo, have come a long way since then, and the support of the tiny English-language paper hasn’t been forgotten.

“He put breath into our struggle. He gave us everything he possibly could,” says the president of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo – Founding Line, Marta Vásquez.

Those were trying times but Cox’s answer was hardly ever “no.” Supported by his wife, Maud, and helped down a very dangerous path by some of his colleagues, his work stands out for more reasons than one.

From beheadings to surveillance, journalists remain the target of people in positions of power. This suggests that words have the potential to change realities, to rattle those very people in power.

Journalism remains worthy and in need of protection. And despite time and distance, stories like the Herald’s remind us of our obligation to avoid the mistakes of the past.