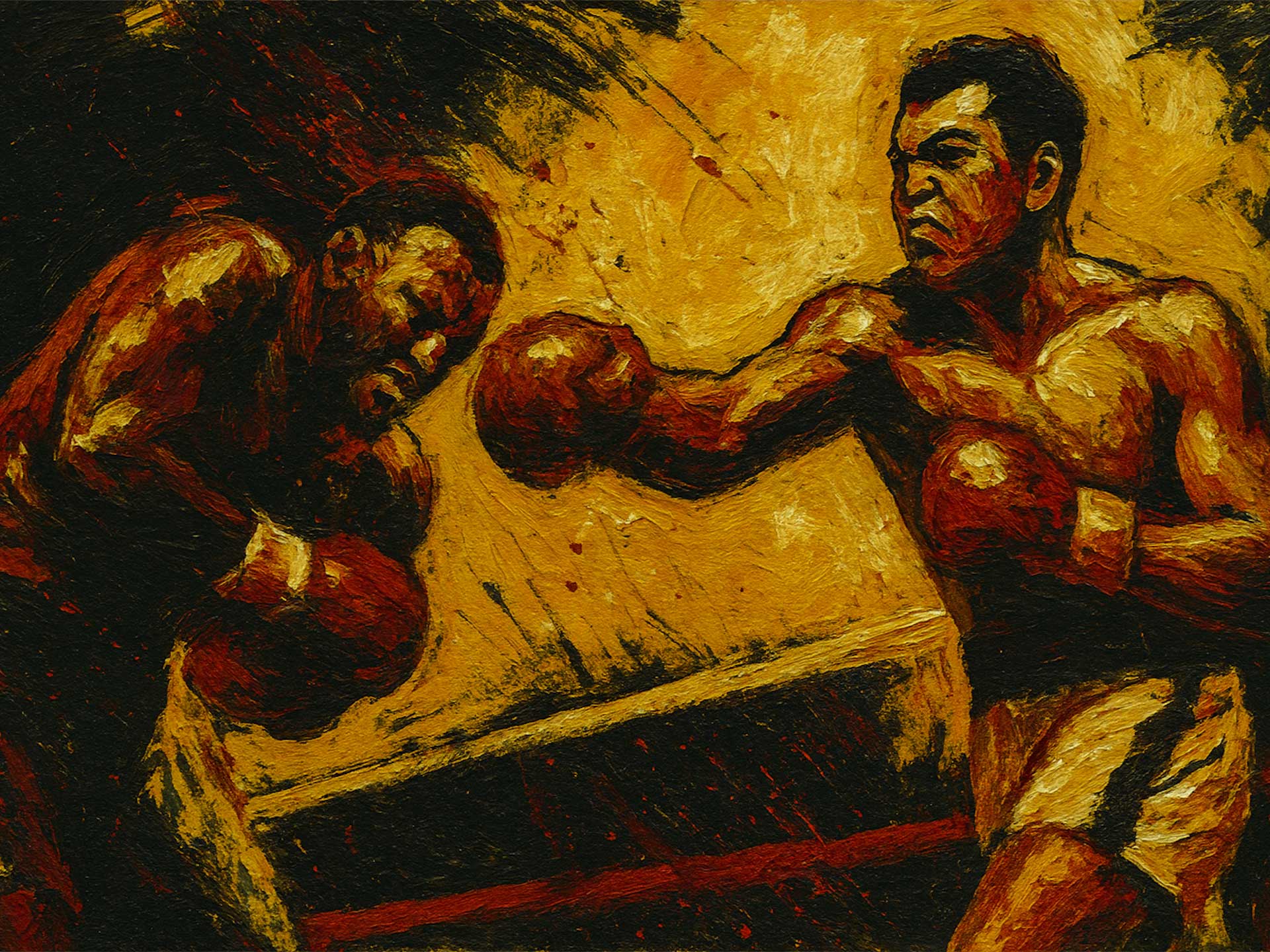

Fifty years have passed since that grotesque yet glorious night that only the unforgiving sport of boxing could offer up: the Thrilla in Manila, the third and final meeting between “the greatest,” Muhammad Ali, and “Smokin’” Joe Frazier. Defined in the twilight of the divisive politics of the Civil Rights movement in the United States, it remains the greatest rivalry in the history of sport.

The score sat at one apiece. It was the conclusion of the previous two meetings — the rubber match and final dance — contested between two titans of the heavyweight division in boxing’s golden era. The WBC heavyweight world championship was on the line. Ali had once again regained the crown, having defeated and dethroned “Big” George Foreman — the juggernaut who had dismantled Frazier to claim the title, only to be bamboozled by Muhammad’s brilliant “rope-a-dope” tactic in a worldwide shock upset.

This final stanza between Ali and Frazier was fought in the Philippines on 1 October 1975 at 10:45 a.m., scheduled to accommodate the 68 countries worldwide who were tuning in. The downside was that, despite the morning hour in Manila, the arena heated to somewhere between 40–50°C (≈104–122°F). The sweltering heat was not simply confined to the arena. The country was also ready to boil over amid an inflation crisis and the 20-year rule of the kleptocrat Ferdinand Marcos, who reportedly financed the promotion with the poverty-stricken nation’s scarce wealth.

Half a century later, what those two men did within the confines of that squared ring on that now-immortal morning of championship boxing has echoed across the decades. Its fabric is etched into the DNA of boxing’s rich, diverse, and ethically contradictory history. Few events before or since capture what it means to suffer — and to inflict — the beating of a rival: the beautiful yet brutal pugilistic poetry witnessed that night.

Upon entering the ring both men had suffered defeats. Ali had suffered his first loss to Frazier four and a half years earlier (1971), at a time when anger and racial division had moved from the streets into popular culture and sporting arenas. His legs had weakened from the inactivity of exile — he was suspended from the sport after refusing to be drafted into the Vietnam War — and he then suffered his second loss at the hands of Ken Norton, who not only defeated him but also broke his jaw in the process. Fueled by emotional energy and a desire to avenge political injustice, Ali adapted and would later avenge both losses.

Frazier had been viciously dismantled by the formidable George Foreman, who bounced him from pillar to post in a one-sided destruction that saw Frazier relieved of his heavyweight championship with relative ease. It’s hard to watch him hit the canvas time and again. To Frazier’s credit, he was down plenty — and then some more — but he was never out: a stubbornness that defined his career and legacy.

The history books will tell us this was a world heavyweight championship title fight. However, to both Ali and Frazier it was more than that. It was a fight to declare the championship winner of the other. No rivalry in boxing has captured the attention of the world like Muhammad Ali and Smokin’ Joe Frazier. Every elite sportsman needs the perfect dance partner — Ali and Frazier were certainly that. Both were Olympic gold medallists, yet that is about as far as the similarities extended: Muslim vs Christian, dissident vs establishment, and Black vs White. The only problem was that Frazier was neither establishment nor white. Yet that was no obstacle to Ali, who described Frazier as a “Gorilla,” “Uncle Tom” and “flat-nosed ugly pug.” One cannot imagine a more racially stereotyped way to describe a proud Black man. But Ali was a showman, and specifics meant little against the interests of promoting a fight by inflaming existing tensions in society — even if that came at the expense of this Black brother, whom he pushed into the archetypal position of a white man’s champion in the public eye.

Ali was more akin to a ballet-dancing poet than a fighter. Standing at 6 ft 3 in, he was athletic and handsome, with a physique to envy. He had the hand speed of a lightweight and the fleetness of foot to make a fight look like a dance. To say he was gifted is an understatement.

Frazier, on the other hand, was much shorter (standing under 6 ft), dark-skinned with thick, trunk-like legs, short arms and a frame that resembled a rugby player. He wasn’t the box of fun that spat poetry like his counterpart, nor was he all that charming in front of a camera. Frazier came from the South, the son of a sharecropper who knew life’s hardships before he could tie his own shoelaces. Nonetheless, Frazier had his own way with words that still have public appeal today: “It’s real hatred. I want to hurt him. I don’t want to knock him out. I want to take his heart out,” he said in the pre-fight build-up.

For a white power structure under threat, and despite the successes of the Civil Rights movement, one can imagine moderately educated armchair racists chuckling at the irony of this social battle being played out between the oppressed themselves as two Black men performed on a global stage. But this was not a stage on which the performers left unscathed; both men would never be the same again. Like honours bestowed upon war dead in conflicts that should never have been fought, terms such as “glory,” “guts” and “grit” serve to romanticise away the damage inflicted on two men who never had any place opposing each other in the first place.

As fitting as that analogy is, the embedded rules of engagement were just as clear. There was no three-knockdown rule per round; the judges scored the winner of a round five points and the loser four. Muhammad claimed a majority of the first six rounds with his lightning-quick, crisp punches that caught not only the public’s eye but also the judges’. From round six onwards Frazier started “Smokin’,” unforgivingly targeting Ali’s torso to slow his mobility. If you watch the fight you can hear the thud of leather on flesh — it’s brutal, but also beautiful to watch him constantly lumber forward, taking lick after lick only to unleash punches sent from hell in response.

Ali threw flurries of punches in bunches with success. When Frazier made him miss, he certainly made him pay, knocking Ali’s head back to generous roars from the crowd each time. Ali’s success came while fighting on the outside at range; his speed and ring craft proved far superior in terms of pugilism. Joe knew this and forced Ali against the ropes, where maximum damage could be delivered. The short arms were an advantage at close range; with Ali’s back against the ropes his fleetness of foot was useless. Frazier had a field day as he pummelled the body and head of Ali — so much so that Ali’s corner screamed at him to get off the ropes and to move!

The “rope-a-dope” tactic used to fool George Foreman was useless against a Joe Frazier who knew how, where and when to pick his shots — and pick his shots he did. This was a war of two men, two styles and a pure, relentless determination from both: determined to crush the other and determined not to lose. As each bell rang at the end of a round, Frazier marched back to his corner, solely focused on the job at hand. His face swelled more and more as each three minutes passed. Ali would slump, arms hanging over the ropes before taking his stool; the signs of the fight and the toll it was taking were plain.

The ebb and flow of the fight in who was winning differed; both had moments of brilliance and domination of the other. Ali would always find a way to rally and halt Frazier’s attacks in true champion style. Frazier absorbed punches as if he enjoyed it, his head being swung from one side to another as Ali unleashed his own unforgiving blows. Smokin’ Joe started to tire and momentum began to swing back in favour of Ali.

Despite Islam being a minority religion in the Philippines — Muslims represent only about 6–10% of the population — some recordings seem to capture someone in the crowd shouting “Allahu Akbar” in the twelfth round (notably, Ali was a practising Muslim). The twelfth was later named The Ring magazine’s “Round of the Year” for 1975, but it was the thirteenth that saw Ali punch Frazier’s mouthpiece clean out of his mouth and into the crowd. Frazier’s face was grotesquely swollen; his eyes had narrowed to slits from the swelling, leaving him unable to pick up Ali’s thumping right hands as they landed repeatedly. Effectively blind in his left eye, Frazier fought through rounds 12–14 with very little, if any, vision.

With a wisdom that can only come from an elder, Eddie Futch — Frazier’s trainer — had seen enough and decided his charge had no business going back out for the fifteenth round. He halted the proceedings. Frazier urged him to let him continue, pleading, “I want him, boss,” but to no avail. Futch had seen all he wanted in the previous rounds: “Sit down, son — it’s all over. No one will forget what you did here today,” he said before signalling to the referee to end it. Muhammad Ali was declared the winner and retained his status as champion. He briefly rose from his stool, raised one arm, then collapsed back down. He later claimed it was the closest he had ever felt to death.

Prior to Eddie Futch halting proceedings, it’s rumoured that Ali had told his corner to remove his gloves before the start of the fifteenth. A former Philadelphia fighter who knew Frazier, Willie “The Worm” Monroe, supposedly tried to alert Frazier’s corner but was unsuccessful before Futch told the referee to halt proceedings. As in all monumental clashes, there is a “what if” moment, leaving fans with questions we will never know the answers to — a mythology both camps would refer to in the decades that followed. The rivalry, unrivalled by any other, had come to an end. To some, it was too early; to others, it came at the right time.

Eddie Futch saved both men that night when he halted the fight — not just from each other, but from the anger born of an establishment structured to end in their destruction. Not unlike the wars that characterised the era, they were willing, armed proxies, put in position to settle other people’s disputes while those same people sat comfortably in their chairs at home and in seats of power. With Frazier fighting blind and Ali on death’s door, neither man knew when to quit — or when enough was enough.

To mere mortals we might think we know when we have had our fill… but Ali and Frazier were not like that. As the mythology goes, they are champions, boxing’s royalty, fistic fight gods, and — if we see things clearly — martyrs: the war dead those terms imply. But cynicism aside, and recognising that such mythology remains the blood-stained stage on which the cogs of our collective history turn, their names will forever ring loud within boxing’s rich history. More than that, their rivalry transcended sport and entered the annals of human history and politics.

Long after the men had hung up their gloves the war of words continued. Joe struggled for years to forgive Muhammad, who, I personally believe, realised the hurt he had caused with his words aimed at Joe — the man who once petitioned for Ali to have his licence to fight reinstated while suspended from boxing for his refusal to fight in Vietnam. Joe even helped him financially during those times. Frazier carried that hurt for many years afterwards. When asked, he said: “Truth is, I’d like to rumble with that sucker again — beat him up piece by piece and mail him back to Jesus…. Now people ask me if I feel bad for him, now that things aren’t going so well for him. Nope. I don’t. Fact is, I don’t give a damn. They want me to love him, but I’ll open up the graveyard and bury his ass when the Lord chooses to take him.”

Later in life Frazier did seem to cool somewhat on the hurt he carried when he said: “The Butterfly and I have been through some ups and downs and there have been lots of emotions, many of them bad. But I have forgiven him. I had to. You cannot hold out forever. There were bruises in my heart because of the words he used. I spent years dreaming about him and wanting to hurt him. But you have got to throw that stick out of the window. Do not forget that we needed each other, to produce some of the greatest fights of all time.”

Ali would later remark, “I’m sorry Joe Frazier is mad at me. Joe Frazier is a good man. If God ever calls me to a holy war, I want Joe Frazier fighting beside me.”

Joe Frazier passed away on 7 November 2011, aged 67, after complications from liver cancer, and Muhammad Ali died on 3 June 2016, aged 74, following years of ill health related to Parkinson’s disease. Ali died a wealthy man, dividing his time between Louisville and a summer home in Michigan, while Frazier died living above his gym in the gritty, working-class streets of Philadelphia. Ali’s memorials were large-scale affairs — tributes from stars and former presidents — whereas Frazier’s funeral was discreet and reportedly paid for by Floyd Mayweather Jr.

Even in death the contradictions and ethical quagmires endure: forever divided, yet inseparable in the story of modern boxing — no serious fight historian can mention one without the other.