‘We are all bored. Putin’s thugs, who represent no one’s interests but their own, are fighting with the liberal opposition, representing the interests of ten percent of the middle class, mainly living in big cities and hating the other ninety percent of the population,’ a friend from Russia told me over a discussion of politics in 2011. ‘This sounds like Ukraine,’ I replied. ‘We have one group of thugs telling tales about the “European dream” and wanting to build a mono-ethnic state, while the other thugs advocate for closer ties with Moscow and exploit nostalgia for the Soviet era. But both of them couldn’t care less about ordinary people.’

In the distant time when this conversation took place, weariness was prevalent among young students, many who perceived post–Soviet politics as an endless deception and spectacle, in which there was no point in participating. Today, such apolitical attitudes are no longer allowed in public in either country while the current war between Ukraine and Russia continues. Propaganda, censorship and military politicisation have now taken the leading position in our societies’ norms. But it wasn’t always like this, was it?

For a long period of time, the term ‘post–Soviet’, in relation to countries that were once part of the USSR, has been criticised by various researchers, activists and artists as incorrect and outdated, because it does not reflect the complexity and diversity of the countries formerly part of the USSR and can produce false binary opposition between “wild East” and “progressive West”. While this criticism is fair, the post–Soviet era in Russia and Ukraine, which ended with Euromaidan and the annexation of Crimea in 2013–2014, nevertheless had its advantages and even its own ‘values’. These values on the one hand consisted of survival, a cynical attitude towards life, and extreme individualism; it was an era of wild capitalism and the absence of ‘we’ as a political, social and universal category. On the other hand, they also included a rational and realistic understanding of political and social processes in the country. ‘Don’t trust anyone’ became the main slogan of the 1990s and 2000s in both Russia and Ukraine.

With Euromaidan and the annexation of Crimea by the Russian forces in 2013–2014, the internal politics of Ukraine and Russia began to produce the most terrible archaism of all that either country had seen since the collapse of the USSR. Russia finally reverted to tsarism with an emphasis on ‘conservative values’ (Russia was moving in this direction even before 2013–2014), while Ukraine took up the idea of creating a pro-Western nationalist state, the essence of which can be expressed in the pre-election slogan of former Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko: ‘Language, Faith, Army’. Both countries’ political agendas prioritised not the values of development and wellbeing of each individual and citizen regardless of identity and beliefs, but rather the values of the State–Leviathan, where each individual is merely a cog in the governmental system.

The strangest forms of this policy can be seen in Ukraine, where certain progressive elements of the human rights discourse have been instrumentalised by the official nationalist agenda – for example, the issues of LGBTQ rights and women’s rights. Since 2014, the visibility of LGBTQ people in Ukraine has increased significantly compared to previous years, and women’s rights awareness is now considered an important component of social and political change. However, the feminist and queer agendas in Ukraine have been fully integrated into the militaristic and nationalist trend, actualised in public discussions mainly through the representation of women and LGBTQ people in the army. Ukrainian nationalism and fanatical pro-Westernism, with an uncritical attitude towards the internal and external policies of Western countries (criticising the West in Ukraine is largely limited to complaints of providing insufficient weapons and support), have formed a framework for the expression of ideas relating to women’s and LBGTQ rights. Human rights discourse has become both militarised and geopoliticised. One famous Ukrainian LGBTQ activist publicly stated, following the escalation of war between Russia and Ukraine in 2022, that she sympathised more with Ukrainian far-right homophobes than with Russian LGBTQ activists.

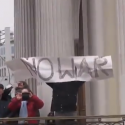

It is always interesting to observe how nationalist and militaristic propaganda contradicts reality and is permeated with hypocrisy. Russia, for example, rightfully accuses the United States and NATO of interventions in other countries and crimes against humanity. However, this does not prevent the Putin regime from intervening and committing heinous crimes in Ukraine. In turn, the officials in Kyiv often speak about Ukraine defending the values of freedom and democracy in this war. At the same time, the Ukrainian government has banned adult individuals with male gender markers in identity documents from leaving the country and has declared forced mobilisation, which, as one can imagine, affects not only those who want and are ready to fight but also those who do not have such a desire. With the onset of the war, Ukraine has essentially turned into a prison for the latter-mentioned category of citizens.

On the one hand, we see Russia, which is fighting against ‘gay propaganda’ and where, in one of its regions, local authorities are claimed to be complicit in the humiliation, torture and murder of LGBTQ people. On the other hand, we see Ukraine, where the government is implementing the so-called ‘decolonisation’ policy. Within this policy, Russian language is discriminated against; there is also a fight against Russian culture and the church associated with Russia. The opinions of the millions of Ukrainians for whom Russian is their native language, Russian culture a part of their cultural self-identification, or the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate a significant aspect of their lives, are simply not taken into account.

Prior to the war, the post–Soviet ‘state of mind’ of Russians and Ukrainians often assumed apolitical attitudes and distrust towards the state. Corruption, societal atomisation and poorly functioning state institutions contributed to this. The causes of these attitudes have not disappeared, but frustration and dissatisfaction with the level of life and with the government’s indifference to the lives of ordinary people have been successfully channelled by both Russian and Ukrainian elites into geopolitical and nationalist disputes. The archaic anti-Western Russian project of ‘returning to conservative values’ met its twin brother in the form of an archaic nationalist Ukrainian project aiming to return the unified and standardised Ukrainian nation to ‘European civilisation’.

The post–Soviet era is the reality for the majority of the former USSR countries, resulting from the arrival of wild capitalism and the emergence of a value vacuum in society. The new political identity of modern Ukraine and Russia is unlikely to solve the majority of the social and public problems that exist in these countries since the collapse of the USSR. Russian and Ukrainian nationalism can only lead to endless war, destroying hundreds of thousands of lives in the process.

The post–Soviet era still entailed distrust of the policy of the country, reluctance to be involved in the dirty games of politicians, and scepticism towards one another’s patriotism. The exception was perhaps the Ukrainian Maidan of 2004, which led to a huge temporary political mobilisation. The fact that the Russian and Ukrainian elites managed to impose projects mobilising state nationalism upon the majority of their populations marked the end of the post–Soviet era.

At one of his lectures, Gleb Pavlovsky, a former Kremlin consultant and subsequently one of the active critics of Moscow’s policy, shared the ideas of Soviet–Russian philosopher Mikhail Gefter about the end of history. According to Pavlovsky, Gefter developed the concept of the end of history even before the publication of Francis Fukuyama’s sensational book The End of History and the Last Man. The essence of Gefter’s concept was that with the collapse of the USSR, the world entered not into a peaceful, idyllic, liberal democratic order, but rather the death of homo historicus. Humanity completes its historical epoch and enters a period of evolutionary survival. All previous human history becomes as an instrument in the hands of one goal – the survival of humans as a species. The historical period was bloody, but the post-historical period has the potential to be even bloodier. In this new era, all previous tragedies, everything that seemed for ever gone, or exhausted, can happen again, only simultaneously, in the context of the paradoxical postmodern coexistence.

When the bloody battles between Russia and Ukraine are compared to the First World War, are we dealing with post-history according to Gefter? When the global confrontation between the anti-Western and Western blocs becomes increasingly clear, are we not finding post-historical parallels with the Cold War? When progressive ideas of women’s and LGBTQ rights in Ukraine mix with the most gruesome militaristic and nationalist archaism, is this not a manifestation of post-historical irony?

A few months ago, a scandal erupted across Ukrainian social networks, caused by the publication of a video of a party of Ukrainian teenagers in a club, having fun and singing songs by Russian performers. The video caused outrage among many Ukrainians, who claimed that it was unacceptable to be using Russian pop music as entertainment while Ukrainian soldiers were dying on the front lines. Several teenagers who appeared in the video responded to these accusations, saying that they are tired of war and just want to live their lives, and that patriotism is not something that resonates with them. I immediately remembered how my friends and I, as teenagers in the post–Soviet era, also had fun with Russian music and recorded such videos. The post–Soviet and pre-post–historical era will not return to Ukraine, Russia, and the world – although I really want it to, no matter how contradictory and ambiguous that era was. It remains to be hoped that these teenagers will not die from Russian bombs or because of the ambitions of Ukrainian or Western politicians.