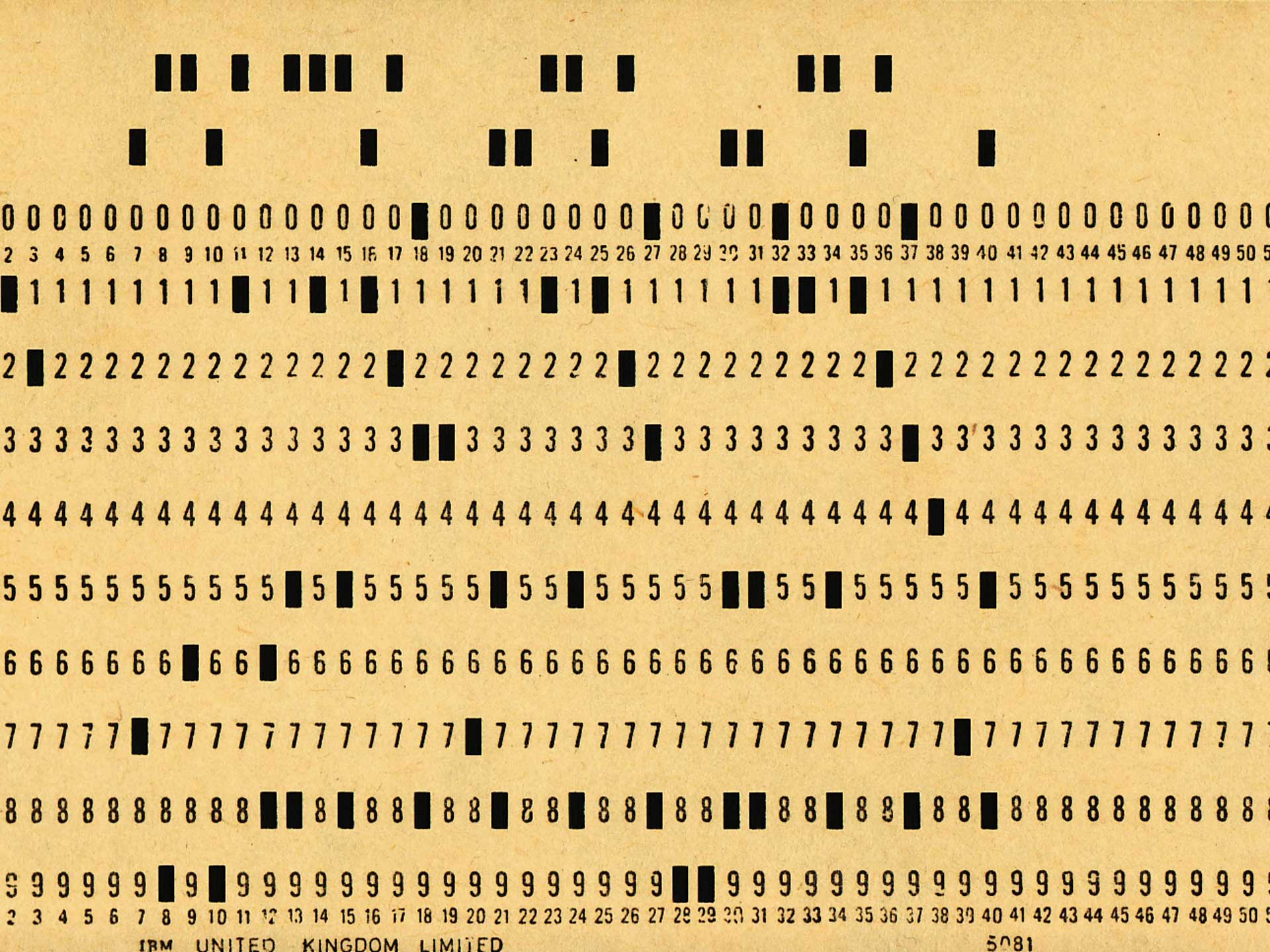

Data isn’t going away. That much is clear. Short of a solar flare, societal collapse or extinction event, data will continue to underwrite the twenty-first century information economy. As digital connectivity increases, so too will the vectors, methods, and types of data expand to further the size and scope of what can be collected. The internet-of-things, biotechnologies, machine learning applications: all promise new and refined insights to churn through the organs of big data to bear ever greater truths about our world.

But the mythology that underpins big data is a different beast. It is essentialised in the West by 21st century marketing neologisms and business jargon: such maxims as ‘data is the new oil’ and the promises contained therein. This mythology posits the world as ‘one big data problem’ and promises the heroic venture into the morass of complexity which envelops reality, from which, underpinned by a positivist ontology and aided by modern computation, a limitless cornucopia of knowledge can be derived. Much like the monolith in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, the big data mythology has propelled an immature and unaware humanity forward through the provision of its knowledge and tools. And much akin to HAL 9000, the fruits of this advancement ultimately proved of great consequence for humanity.

The big data mythology has been sustained by an enormous investment of faith by the global economy since the era of the iPhone 1 and Facebook. It has informed the norms, preconceptions, and behaviors that serve to maximize data collection, storage, and use. An interconnected clergy of actors has been responsible for selling this salvation. At its apex: big tech, though governments and broader industry have too played their part. But as big data has matured, many of its auspices – heralded at the flourishing of the information age – have ultimately been unveiled as shortsighted, reflexive, and naive.

The sins of big data

It did not take long before big data’s offering of bespoke, individualized user service, such as curated social network feeds and tailored advertising, was hijacked and amplified to fuel a regime of surveillance and addiction. The realization that the worst excesses of human psychology maximized user time-on-site was quickly capitalized upon by all manner of interested parties, including political consultancies, marketing agencies, and more to drive engagement, influence election outcomes, and supercharge consumerism. The innate human susceptibility to addictive feedback loops and to material that inspires hatred, division, and controversy, in its worst manifestations, has been weaponized to initiate interpersonal grievances, instigate the persecution of minorities, and sow demoralization across the world’s democracies.

Those trace elements of online user interaction, left by every minute act or non-act on a digital medium, helped form vast yet intricate mosaics of the human experience of billions. Entire portraits of individuals could be compiled across data ecologies, enabled by a rapacious, unmoderated disregard for user privacy in a digital world gone mad. The founding libertarian vision of the internet had, in a way, been fulfilled – though perhaps not in the manner initially conceived. Cyber-Hobbesian anarchy gave rise to titanic virtual sovereigns that have usurped and, in some cases, imbricated themselves with, the state. The infrastructural power key to these entities’ success – the proprietary platforms through which the data is coursed – continues to afford them unrivaled dominion over the information space.

Yet the great irony remains that, despite the incalculable volumes of bits that have been sacrificed at the altar of the big data monolith for the bestowal of data-driven insights, the technologies big data has exploited and enabled, as well as those that have enabled it, have produced the converse: a global information ecosystem deluged in falsehood. The epistemic commons has been torn asunder, and our capacity to discern truth from falsehood consequently diminished. Of course, big data thrives in this chaos and opacity, offering a way out of the cave for a fee.

The ‘science’ of big data

The big data mythology has posited its namesake as a superior science to the epistemologies that preceded it. It rests upon the presumption that computation is inherently advantageous to cognition, and that a datum stands as a positivist ontological referent for reality. Yet, this science has proven itself to be less a faithful exercise in the advancement of human knowledge, and more about the control and profitability associated with the identification, definition, aggregation, analysis, and inferencing of data.

At its core, big data seeks to subordinate the phenomenal world to computability. Here, it can divine – through its black box crystal balls – the myriad political, economic, environmental, and social trends worth a buck. It’s hard to argue with its sample size, too. Any finding postulated by big data is often given a priori credence based purely on scale. This scale is how it attempts to elude the fickle unreliability of human cognition. Though it is often said that big data ‘speaks for itself’, its innate value lies in how ‘raw’ data can be fashioned into a narrative worth selling. “Torture the data long enough and it will confess to anything”.

Shifting sands

Though the big data monolith has remained firmly planted as the sacred object of the information economy for decades, there are continued signs of its withering. Repeated failures by the world’s public and private organizations to responsibly own, use, and protect data has drawn increasing scrutiny and ire from populations to whom mass data aggregation are subject. Emerging cybersecurity risks, dawning technological obsolescence, and growing calls for regulation are three such empirical factors that are beginning to test the primacy of the big data mythology.

(1) No rules of engagement

The cyberwar is now waged universally, surreptitiously, and asymmetrically across every corner of the internet. What used to be the reserve of intelligence agencies and uniquely talented hackers has now become democratised to a population of digitally native threat actors which knows no jurisdiction and, often, is constrained by no ethical guardrails. Though money or geopolitical gain is often the ends of their pursuits, it is almost always the case that data stands in between.

This intensifying cyber risk is forcing organisations to reconsider the scope, extent, and security of their data collection, use, and storage. Those organisations with the largest concentrations of sensitive data: government entities, healthcare, telecommunications, financial services, and legal firms are increasingly suffering major data breaches and ransomware attacks across the globe. These attacks have never been easier to pull off. Otherwise shielded by skyscrapers, offshore bank accounts and squads of lawyers, today major corporate entities can be brought to their proverbial knees by a sole employee’s errant click on an email attachment. No amount of cyber defence can completely protect organisations from the soft, fleshy problem.

When organisations are hit, it is often not known where affected data is stored or what security protections are afforded it. ‘Data governance’ is growing in prominence in the wake of these events as governments and companies the world over recognise the worth in knowing what information they have, where it is stored, who has access to it, and how secure it is. Data mesh, data lakes, data warehouses, data lakehouses: entirely new technical architectures are being offered to service the need to store, use, and protect information well. Where there is a dearth of a clear business need for owning data, it is increasingly being culled. How we’ve run a global information economy for thirty years to this point without knowing where things are is astounding.

(2) Date lean tech

Though many new technologies work in service of the big data monolith, there are also those which appear to be displacing it. Innovations in digital identity seek to standardise the disparate technical frameworks that govern information exchange on internet applications. Implemented correctly, digital identity would eclipse the need to indefinitely surrender one’s personal details: emails, birthdate, address, etcetera – but would simply be posed a one-time query to temporarily access certain information such as ‘are you over 18?’. A central repository within which person’s personal information is contained would then dispense only the requested data to the transacting platform. In parallel with the push towards implementing zero trust architecture, wherein user authentication is required at every level of a digital transaction as is practicable, piloting states could potentially secure and minimise the global exchange and storage of personal information. Blockchain, too, offers hope in this regard.

Even those technologies which owe their existence to big data may forsake their birthright. Diminishing returns on the efficacy of large datasets in foundational machine learning models could potentially burst the hype bubble in which the technology has remained aloft for the past year. When these models are trained on their own synthetically generated data, they experience a form of autophagia, whereby their capacity to produce synthetic content itself degenerates. As more and more synthetic data percolates onto the internet, machine learning firms will increasingly need to monitor the nutritional content of that which they feed models. Hoovering up vast sums of internet data, such was the approach adopted by OpenAI to build ChatGPT, might prove impracticable going forward. In this way, and rather ironically, big data risks becoming an existential threat to AI. There are also signs that future machine learning models might not even require the quantity of data and computing power needed at present to sustain their effectiveness, potentially resulting in a methodological pivot in the ways AI is constructed at scale. Who could have guessed that focusing on technique rather than supersizing datasets would yield a more refined product?

Beyond AI looms the spectre of quantum computing. The vast sums of money that have been thrown at quantum by nation-states in the last few years – with China far exceeding that of the rest of the world – should flag the technology’s political, economic, and strategic significance. Quantum decryption, whereby the concentrated power of a quantum computer is channelled at cracking an encrypted asset, could potentially negate many standard data protection methods. Though we may be decades away from the prospect of strategic use of quantum computing, threat actors are currently engaged in the theft of encrypted information right now for its eventual decryption via quantum. The only surefire way to protect information in the quantum age or even preceding it? If it doesn’t exist.

(3) Rage against the machine

Lastly, growing regulatory pressure – sourced from global public discontent convergent with the above-mentioned drivers – is threatening the near limitless freedom big data actors have enjoyed in their indiscriminate data scraping for nearly two decades. The public, now acutely aware of the scope and extent of modern data collection practices, as well as the value and security risks associated with the information held about them, is increasingly expecting more socially responsible behaviour from holding institutions.

The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), by introducing the concept of adequacy for data exchange, has effectively already paved the way for global data reform from as early as 2018. Though not entirely unproblematic, it could soon be accompanied by AI and data privacy reform both within the EU, and in other jurisdictions such as Canada and Australia. These statutes could prompt reforms in other countries, further advancing the global pressure on organisations to act more responsibly in their collection and use of data. States are also experiencing growing calls to support Indigenous data sovereignty, which could here be reflected. Greater regulatory impost has been flagged, too, by the US’ 2023 National Cybersecurity Strategy, which seeks to ‘rebalance the responsibility to defend cyberspace’ unto those who are asymmetrically more capable of acting. Those who have more data will be increasingly expected to govern, use, and protect it well.

Regulatory pressure may also emerge in service of reducing energy use. The volume of energy expenditure necessary to support global data storage and utilisation is anticipated to increase exponentially over the next five years, potentially exceeding that of entire nation states. This will likely place a premium on the use and storage of data and machine learning models, forcing alternative practices and data minimisation.

These three empirical drivers: cyber risk, technological change, and regulatory pressure, indicate that big data is fast proving a liability more so than an asset. The limitless and carefree collection, use, and storage of excessive volumes of insecure and poorly managed data is rapidly becoming prohibitively expensive for actors in the information economy. The cost/benefit analysis of holding large quantities of data will soon be overwhelmingly biased towards the former.

Discursive and epistemic upheaval

Yet empirical factors may not be wholly sufficient for eroding faith in the big data mythology. While increasing cyber risk, technological change, and current institutional and regulatory levers will likely disrupt modern data collection practices, they may not be adequate for altering them sustainably into the future. If the global economy’s approach to ecological collapse is any indication as to how contemporary global challenges are collectively addressed, then it will require a reframing of the conceptual grounds on which big data is perceived and discussed for meaningful change to be effected. The hegemony of big data will need to be challenged.

Such a global discursive and epistemic shift to the ways in which we perceive the world and in our relation to data is, in many respects, already taking place. Academic scepticism and critique of the big data episteme is not new, though its translation into more mainstream discourses is starting to gain renewed purchase. David Hand’s work on dark data, that which we are unaware of or is not easily captured, measured, or quantified, but nonetheless bears considerable meaning on the ways in which we interact with the world, is an important model to integrate into one’s apperception. Dark data is complementary of Nicholas Nassim Taleb’s much-referenced work on black swan events, those which we cannot prepare for based on our preponderant ignorance to their catalysing circumstances. Both attend to Rumsfeld’s unknown unknowns which, by all accounts, comprise the nigh-infinite majority of knowledge categorisations that make up phenomenological experience. No amount of data or Bayesian inferencing can, at present or indeed into the future, attend to this problem set.

Reframing the ontological and epistemic confines by which we can come to know things can aid in the provision of more sensible solutions to some of our most pressing challenges. It also protects us from succumbing to the hype machine Silicon Valley is so well-versed in driving. Reconceptualising data itself, for example, as something inherently relational, transient, and ethereal, rather than analogising it to physical property and situating it in a logic of individual rights, might position us better to regulate it more effectively.

Ozymandias

Increased cyber security risk, burgeoning technological obsolescence, and growing public discontent indicate the potential death of the mythology that has sustained big data for two decades. Underpinned by a global discursive and epistemic transformation in the ways in which we understand our relation to data and to knowable experience, this shift is likely to be accelerated.

The data collection practices of the future appear less dogmatic – less obsessed with its maximisation, and more considerate of its implications for privacy, security, and authentic value. Though datasets may remain ‘big’ by any objective measure, they will lack the frivolity and obfuscation which currently inform their capture. Less will truly be more in the post-big data age.

The big data monolith has set its foundations on sand. As the sands shift towards a new era, the fragility of the monolith is laid bare. Beyond this broken edifice dawns the possibility of a more responsible, secure, and dignifying future for data collection, storage, and use: one in which the subjects of data reserve greater agency and security concerning the information held about them. An information age reformation could well be taking place.

All views expressed are those of the author alone.