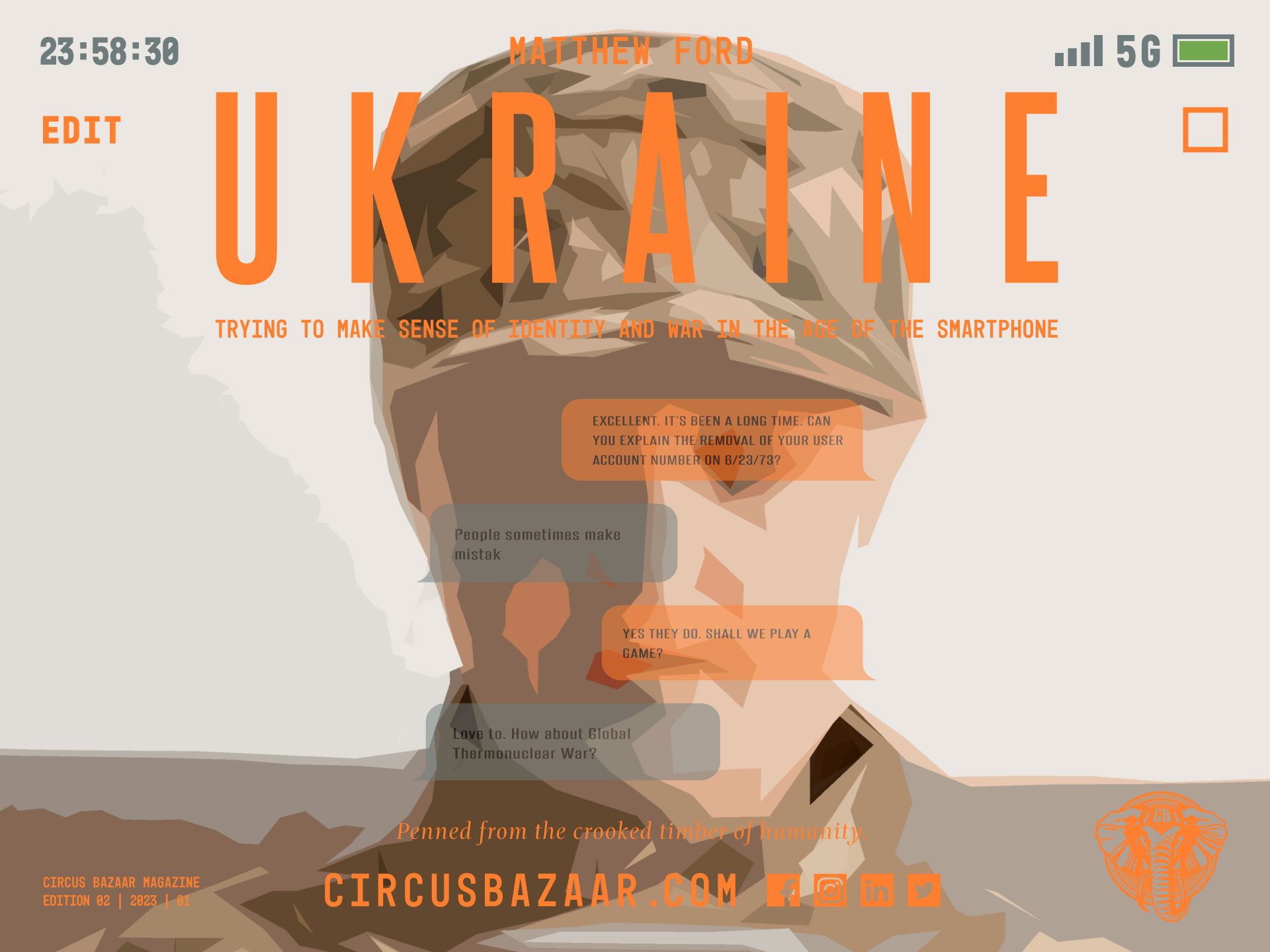

Ukrainian identity is being reinvented by war. Ukraine’s Ministry of Culture and Information Policy has helped to orchestrate this reinvention through social media campaigns – #standwithukraine – while engaged in a daily struggle against Russian cyber attacks and direct artillery bombardment. At the same time, self-organising groups like the North Atlantic Fellas Organisation seek to limit debates that might undermine Ukrainian messaging. In between the meme wars and the trolling, an image of Ukraine emerges: battered but defiant. Stoicism and resilience in the face of Putin’s extermination. Such messages may resonate with Western populations. Beyond the West, the smartphone delivers Russia’s propaganda to a global audience.

The smartphone represents the manifestation of a complex ecosystem of information infrastructures. As a device for recording the ‘now’, the smartphone adds geolocation to videos of events. It has limitations, if belligerents switch off the internet, but both sides recognise that it is vital to society, government and the conduct of the war. The internet makes life in the warzone possible, enabling the fighting and supporting Russia’s population engineering in the occupied zones. The smartphone is changing events, reformatting their representation, manipulating users’ thoughts, and redefining how the war is being fought. Consequently, the war in Ukraine is the most connected conventional conflict in history.

Compact and handheld, the smartphone helps soldiers connect to family at home, relax with a game and catch up with events. For civilians, the smartphone enables refugees outside Ukraine to maintain contact with the homeland. With one device you can access the government, amplify the war, kill the enemy, donate to crowdfunding campaigns, and collapse the frontline and the home front. Soldiers use phones as controllers for their drones, helping them to adjust artillery fire on to targets. Ukrainians caught up in the occupation zones risk taking photographs of Russian movements. Social media influencers use them to spread warnography and disinformation. Handheld smart devices provide the technology platform for battlefield target identification, coordination and prioritisation software. Energy grids and electricity supply are limited, forcing a critical choice upon soldiers and civilians alike: turn on the lights or power up the smartphone?

In the first year of Russia’s full-blooded invasion of Ukraine, the war appeared at first to resemble the iconic conflicts of the twentieth century. Images of tanks and airpower recalled the old Second World War newsreels, while trenches and Maxim machine guns evoked even older Great War imagery. Yet neither analogy does justice to the lethality of the Ukraine battlefields, the brutality of Russian occupation, or the way digitisation saturates every aspect of the fighting.

This digital saturation is self-evident in virtually every video of the frontlines. Soldiers carry smartphones alongside their assault rifles. They record themselves fighting and dancing, distributing the footage for memes and propaganda. Ukrainians do this and a Western audience views the videos on social media. (The Russians do the same and all Westerners hear is how the Russians have stupidly given away their positions and then been targeted by Ukraine’s artillery.) Offering the means to produce, publish and consume information anywhere in the world, smart devices are the essential, ubiquitous, and subsequently mundane civilian technology platform of the twenty-first century, and one that has now been adapted for war. These changes reflect a new geometry of power that is transnational in nature, underpinned by information infrastructures that are rarely considered or reflected upon. This is not just a matter of Elon Musk’s Starlink low orbital satellite technology, but is also related to the plethora of other systems that make the internet possible.

Inevitably, this is challenging the existing ways of making sense of war. The smartphone is collapsing the once distinct categories of soldier and civilian into the shared realm of participant, enabling everyone to engage in the fight, no matter where they are in the world. Working via various Telegram channels, including the 350k-plus subscribers to the IT Army of Ukraine feed, the Ukrainians crowdsource information operations, successfully shaping the West’s media narrative. Scripted in advance, there is no surprise that the opening weeks and months of the war were dominated by discussions on a no-fly zone and the Finnish-Soviet War of 1939-40. So successful were these information campaigns that senior Western academics and commentators parroted the talking points without much scrutiny. This approach chimed with those who wanted history to provide easy guide rails for current events, but neglected to take into consideration the ways in which the narratives were being manipulated for the ready consumption of audiences needing digestible answers.

Both the emerging practices of war and the manners and methods of its representation constitute a paradox. The technologies that shape our approaches to understanding the fighting in Ukraine are transnational in nature, but some of the most dominant messages that emerge from these platforms reflect the reinvention of Ukraine’s national identity. The messaging is subject to algorithmic intervention, leading to a variety of outcomes. For instance, on several mainstream social media platforms, violence is downplayed. By contrast, on Telegram the violence is unrestrained and brutal, breaking all the norms of mainstream media reporting, but has become mundane in its regularity. In this new paradigm, the war is not an anomaly limited to Russia and Ukraine. Rather, it reflects a fundamental shift in the operation of government, the definition of geopolitics, and the ways in which identity is forged when forms of violence are widely available online.

When it comes to government, for example, transnational information infrastructures are constructing a new digital sovereignty. Prior to the 2022 invasion, Ukraine’s government bureaucracy had a physical presence located in sovereign Ukrainian territory. Now government services are hosted by Amazon Web Services in the cloud, on servers outside Ukraine. Only by going online can one access the services that previously required a visit to a government office. Once controlled by employees of the state, Ukraine’s future is now bound to the internet service giants that power much of the world’s networked economy. Even if Ukraine ceases to exist territorially, it will survive as a virtual space with a global diaspora dispersed around the world. The future memory of Ukraine will have a life regardless of the outcome of the war.

This potential hauntology of Ukraine tells us something about identity in the contexts between memory, conflict and contemporary technology. Where in this conglomeration of socio-technical systems does Ukrainian identity begin and end? On the battlefield? In the amplification of memes? In some future cyberspace? With mainstream Western social media platforms restricting Russian access, we watch the façade of the internet as a global commons being torn down. Russia likewise is trying to cut off access to Twitter and Facebook. Now splinternets are the order of the day. Will the new identities forged in war become known in future to those living on different informational grids – or will we remain locked within our own media ghetto for ever?

When it comes to fighting, the implications of the war have stretched the utility of the smartphone beyond the realm of information operations. Now the smartphone shapes the conduct of battle, making it hard to define where the battlefield starts and where it ends. Indeed, this new ecology of war has not been properly quantified. Civilians from a neutral country on the other side of the planet can help with targeting data for Ukraine’s intelligence fusion cells just as easily as can Ukrainian citizens on the frontlines. Targeting is itself now outsourced to private companies crunching open-source information and working alongside Ukraine’s armed forces. This complex stack of interlocking socio-technical systems increases the attack surfaces available for kinetic and cyber attack. Are these people or organisations legitimate targets for Russian strikes? What about the data centres and the satellites, the cellular networks and the undersea cables?

If Ukraine shows us that anyone can participate in war, then what happens to the bystanders? This question is not limited to people at home amplifying social media messages, but also includes the possibility that ordinary civilians can participate in targeting adversaries simply by processing open-source information. Yet civilians are not restricted from participating remotely. On the frontlines or while under occupation, noncombatants can photograph and geolocate the enemy, then pass that information on to intelligence fusion cells. At the same time, soldiers are using the same technology to develop the necessary situational awareness to locate enemy units and target them with artillery. Can these civilians now be regarded as combatants in the same way as soldiers, just by dint of using the same software and devices? The implication then is that the differences between soldier and civilian, armed forces and society have collapsed. To be provocative – in this new world, you cannot be a bystander if you carry a smartphone.

Even if the warzone could be properly delineated, making sense of what remains creates its own challenges. The increased datafication of the battlefield has led to an explosion of data points on the war. Ten years of civil war in Syria has reportedly generated 40 years of footage. In comparison, the first 80 days of the 2022 invasion of Ukraine has generated 10 years of footage. In these circumstances, thinking through the global implications of the war in Ukraine with regard to identity and future geopolitics tends towards re-hashing twentieth-century historical analogies. Clearly, the old and the new sit alongside each other even as this war is being prosecuted. When it comes to explaining the evolution of ideas, it nonetheless must be conceded that there is something very revolutionary going on in Ukraine. It implies a radical rupturing with the past.

These changes need to be further contextualised against the emergence of a new digital sovereignty, where the bureaucracy’s physical presence is limited, and government services are only available online. In these circumstances, it might be appropriate to question what remains of Clausewitz’s famous trinity of state, society, and the armed forces. Are we left only with the ontological core of Clausewitz’s claim that war is fighting? Although this ontological claim still has resonance, much of what defines war – and not just its character – surely needs re-examining. For the very way in which war and its representations are made known to us has fundamentally changed. War in the twenty-first century has gone through the same epistemic revolution that has affected much of the rest of society, as it grapples with the changes brought about by the fourth industrial revolution.

The culture of war: how we know about war, how war is organised as a social activity, and how war connects back to the traditional structures of state, society and the armed forces will require recalibration. This is not to imply that everything is now different. Rather, it is to argue that we need to carefully contextualise and understand the dramatic changes that the war in Ukraine has produced. That is to say, we must test how radical the breaks are with the past, recognising that this war is certainly different from previous wars. Much of what is new on the battlefield reflects wider changes in society and its relationship to connected technology and work. In their obsession with artificial intelligence and the latest wunderwaffe, defence intellectuals have forgotten to pay attention to wider changes in society. These changes are not concerned simply with identity politics but also with the technologies that now frame the ways in which people make their living. The gig economy is here to stay. The question for armed forces is how these changes will impact them, not just in terms of who they might recruit, but in the ways that they come to know and fight war.

This question is especially important given that identity formation in online environments has a different dynamic to society’s traditional methods of creating a shared sense of community. Social media connects people across the world, driving politics in ways that do not always immediately relate to a particular nation. Traditional forms of identity formation (i.e. through remembrance and shared historical understanding) struggle to be heard in contemporary social media spaces. War in Ukraine has forged cohesion into Ukrainian society. Conversely, Western citizens are struggling to sustain their interest and/or attention in the context of a fragmented media ecosystem and a cost-of-living crisis. In this context, the war in Ukraine may yet produce the shattering of resolve among Western nations who otherwise wish to hide the dramatic geopolitical consequences of Russia’s invasion.